The Gift of Love...

The Gift of Love......the 19th Century.

The ceuntury opened with woman, demure and decorative, fragile and revered, well established upon her pedestal. Queen Victoria painted by Franz Xavier Winterhalter on her wedding day. "I wore a satin gown with a very deep flounce of Honiton lace, imitation of old. I wore my Turkish diamond necklace and earrings, and Albert's beautiful sapphire brooch." recorded Queen Victoria in her journal on Monday,10th February, 1840. The jewellery matched her idealised status... pretty, feminine, sentimental. Symbols of love, hearts, crowns, flowers, followed her from the previous century. So too did the memorial ring. Portrait rings carried the loved one's likeness, executed in exquisite details. Hidden in lockets, brooches and rings, were locks of hair, lovers' or childrens', which were tenderly cherished.

But alongside this delicate and appealing jewellery of sentiment, jewellery had an important role as a status sybol in the 19th century society.

The Industrial Revolution made money for many. The successful businessman showed off this newly accquired wealth in public by loading his wife with jewellery.

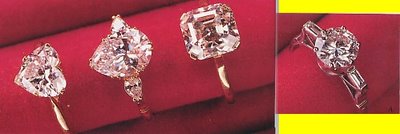

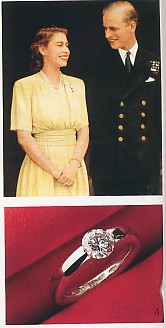

Diamonds became increasingly sought after. In 1870 supply met demand with the great discovery of diamond mines on the African continent. At a stroke, the status symbol of the diamond became accessible to a far wider public. For more and more young couples a diamond engaggement ring, usually a solitaire or a combination of several smaller stones, was first choice.

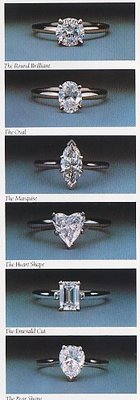

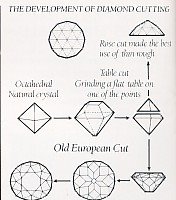

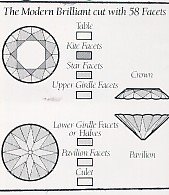

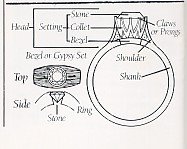

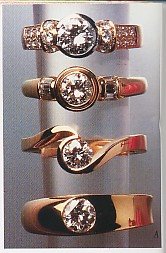

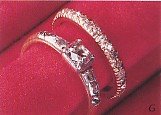

By this time it was established that a bride could expect two rings: a gem-set engagement ring, and the actual wedding ring which, in Victorian times, was no more than a slim gold band. Trade catalogues of the time show the immense variety of designs available, some for as little as 2 pound. These are solitaires, half hoops, double or single clusters, fan, panel, navette, cross-over or 2-part designs such 'Toi et Moi'. The brilliant cut was dominant. Peruzzi, a Venetian cutter, is attributed with inventing the first version of this 58-facet cut; but only in the 19th century was the brilliance and power of the diamond fully revealed.

The rich new supply of rough diamonds influence design, emphasis passed from the setting to the stone itself. The single, immaculate diamond became the height of fashion... and the revolutionary new Tiffany mount made this more feasible than than ever before.

Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning's Diamond Engagement Ring perhaps Robert Browning was thinking of this ring when he wrote these words:

"... on the finger which outvied Still by fancy's eye described, In token of marriage rare: For him on earth, his art's despair, For him in heaven, his soul's fit bride."

Lines 286-291 of "James Lee's Wife" from Robert Browning's Dramatis Personae."

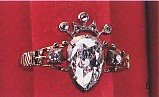

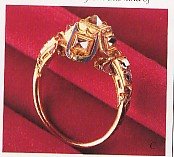

The sentiment expressed by the 18th century style of acrowned diamond heart continued to appeal to lovers in the early Victorian period. This ring was chosen for the romantic marriage between the poets Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning in 1846. After their marriage they moved to the Casa Guidi in Florence, Italy.

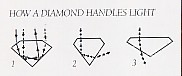

Tiffany, the famous New York jewellers, invented a dramatic open setting with plain metal band, where the stone is suspended by 6 tiny platinum claws or prongs, platinum having the exceptional property of great strength even when finely worked. This setting allows the fullest play of light to the exposed stone from each facets. Unlike the ols-style setting covering all but the face of the stone, where flaws could pass undetected, the Tiffany mount was a fine means test of a diamond's quality, giving the cut, colour and clarity a new importance.

Throughout this prosperous century, no-one enjoyed jewellery more than Queen Victoria. She had an immense collection and spent many thousands of pounds with her Court jewellers, Garrard. In 1850, her collection was crowned by the Koh-i-Noor ('Mountain of Light'), then the world's largest diamond, a gift from the East India Company.

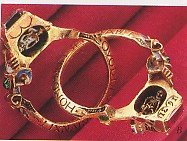

Possibly one of Queen Victoria's favourite piece was a simple enamel band set with a single diamond, given her by her beloved Albert four years before they married. Later, for her official engagement ring, Queen Victoria chose something less demure - a snake ring. Snake rings were favourite 19th century symbol. The coils, would round into a circle, symbolised eternity. Superior versions had diamond heads and eyes.

The 19th century saw far-reaching changes in jewellery design. First, dedicate and imaginative sentiment ruled. In the 1860's the docile woman on the pedestal stepped down in favour of the vote, education, and the new freedom; jewellery corresponding became large, bold and assertive. At the close of the century, a romantic free-thinking spirit emerged and Art Nouveau brought a fluid delicay back to design.

Throughout all the changes, the vivid beauty and indestructibility of the diamond ring continued to be the ultimate symbol of love and hapiness.

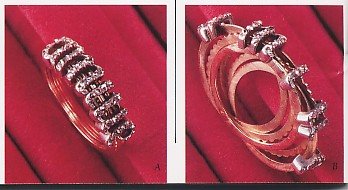

Inn addition to the use of the keeper ring to hold the diamond rings, the brilliant diamond cluster enhanced by the mazarine blue ground, neatly bordered with white enamel. The compact shape and broad hoop indicate that this ring dates from the early 19th century.

There are also beautiful band of graded diamonds is typical of jewellery fashionable at this time. Sadly, this particular example is a memeorial ring for Admiral Frank Sotheron who died in 1839 but the rings of similar design would have been used for betrothals and weddings.

To add to the famous rings during this century; the ring with symbol of hands holding a heart continued to appeal well into this century. The heart in this ring is set with a clear and brilliant diamond and the mitre shaped crown surmounting it indicates a Russian origin. Two beautiful hands gloved in diamonds present it to our view.

Portraits of loved one have been treasured token for many centuries, for example Henry VIII sent his miniature to Anne Boleyn with the message:

"I send you the thing which comes nearest that is possible, that is to say my picture..."

This ring shows a delicate portrait of a very sweet lady beneath a large flat diamond. It is likely that the central part dates from the 18th century and was enlarged in the 19th century by the outer circle of large brilliant, sparkling diamonds, to suit the fashion of time.

There were also the rings that were with the hoop broadened out to a wide bezel pave set with rose-cut diamonds in silver collets, as early as the 19th century.